Let's clarify. The wings of the nose are two paired cartilages, which, located at the base of the nose, actually form the nostrils.

In some cases, plastic surgery of the wings of the nose is a truly effective way of transforming an unattractive nose into a completely attractive one and correct in terms of proportionality in relation to other parts of the face. Moreover, without serious surgical intervention affecting bone tissue and requiring long-term rehabilitation. Of course, this option is not suitable for everyone, but only for people who:

- the wings of the nose are excessively long, thereby greatly lengthening the nose;

- the nostrils are characterized by excessive width (even when the back is narrow), which makes the nose as a whole wide and not very neat;

- the nostrils are narrow and disharmonious with the rest of the nose and the face as a whole;

- there is asymmetry, congenital or acquired deformation, recession of the nostrils;

- the nostrils are excessively thick due to an anatomical feature when the skin or cartilage tissue is thickened.

Correction of the wings of the nose can be an independent operation or one of the stages of complex rhinoplasty. If necessary, the surgeon recommends performing septoplasty during the operation if there are difficulties with nasal breathing due to curvature/displacement of the nasal septum.

How do you know if nose wing correction alone is enough in a particular case? Come for an appointment with our specialist. The doctor will conduct an examination and determine the optimal intervention tactics, after which the nose will take on the desired appearance and will no longer spoil the appearance.

The list of contraindications is limited to “standard” conditions and diseases for which it is advisable not to use general anesthesia (if local anesthesia is used, they are not taken into account). In addition, correction of the wings is not carried out in the presence of inflammation and unhealed soft tissue damage on the outside of the nose and in the nasal cavity.

How is the operation performed?

Correction of the wings of the nose is a relatively simple operation, as is already clear from the above, and can be performed under general or local anesthesia. Intervention tactics are determined in accordance with the problems that need to be eliminated. Most manipulations with the wings are performed through open access.

Reducing or shortening length. Wedge-shaped (most often) crescent-shaped or oval incisions are made at the base of the nose, after which excess cartilaginous structures and soft tissues are excised, and finally sutures are applied.

Narrowing. Sutures are placed on the columella, or rather in its lower part, which are then tied, and excess skin is removed. As a result of simple manipulations, a scar is formed, evenly pulling the soft tissue towards the center.

Retraction correction. A support is created for the wings; for this purpose, surrounding tissues are mobilized and autocartilage is transplanted, which are the person’s own cartilaginous structures extracted from the auricle or from the nasal septum. Sometimes skin grafts are required.

Contraindications for rhinoplasty

Rhinoplasty is one of the most complex operations, so before performing the intervention, the doctor will evaluate the presence of all possible contraindications. These include:

- diabetes;

- severe pathologies of the heart and blood vessels;

- chronic infections (tuberculosis, syphilis, brucellosis, Lyme disease, etc.);

- immunodeficiencies;

- blood clotting disorders;

- autoimmune pathologies;

- allergy to components of anesthesia and anesthesia;

- liver diseases;

- oncological diseases.

The operation will be temporarily postponed in the presence of acute respiratory diseases, febrile conditions, acute rhinitis, sinusitis, exacerbation of herpes, inflammatory skin processes in the face and nose.

Examples of completed work

Higher Attestation Commission / Annals of plastic, reconstructive and aesthetic surgery. No. 2. 2015 Moscow. Page 33-40 / Glushko A.V. , Drobyshev A.Yu., Pavlyuk-Pavlyuchenko L.L., Gordina G.S.

Introduction.

The main protocol for surgical treatment of patients with congenital anomalies of the dentofacial system is double-jaw surgery (orthognathic surgery). Typically, it consists of a LeFort I Osteotomy of the maxilla and a Bilateral Sagittal Splitting Osteotomy (BSSO). This surgical protocol makes it possible to fully move both jaws relative to each other and relative to the structures of the facial skeleton in order to achieve the best functional and aesthetic results. The protocols described above are standardized and widely used by surgeons around the world.

One of the unfavorable consequences of orthognathic surgery with an aesthetic component is a change in the structures of the external nose, which occurs due to the peculiarities of the osteotomy of the upper jaw and its movement [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. In particular, the perioral and paranasal muscles are dissected with a significant detachment of soft tissues, a wide detachment of the mucous membrane of the bottom of the nasal cavity with cutting off the cartilaginous and bone parts of the nasal septum from the nasal spine of the upper jaw. Next, complete mobilization of the jaw occurs, followed by its movement. As a result, there is an expansion of the base of the nose, often an increase in the projection of the end of the nose, flattening and thinning of the upper lip, which can have a negative impact on the patient’s appearance and worsen the aesthetic result of the surgical treatment.

Of course, it is worth noting the fact that the severity of these changes depends on the characteristics of the patient’s soft tissues, the surgical technique, the amount of movement of the upper jaw, as well as the use of special surgical techniques to prevent or reduce these negative consequences (3, 4, 9, 10).

In their arsenal, surgeons use a number of surgical techniques that are aimed at reducing or preventing possible postoperative changes in the external nose. The most common one, also used by us, is the technique of suturing the base of the wings of the nose, known as the Alar Cinch Technique (11, 12, 13, 14). In some cases, a number of other techniques are also used, for example: excision of the anterior nasal spine, deepening the floor of the nasal cavity, sectoral excision of the wings of the nose, or, in some cases, plastic surgery of the terminal part of the nose [12, 15, 16].

But despite the use of the methods described above (with the exception of plastic surgery of the terminal part of the nose), which help to correct changes in the base of the nose that occur during the movement of the upper jaw, the final result still remains very unpredictable.

Separately, I would like to emphasize that in the postoperative period, some patients pay attention to changes in the width of the tip of the nose and suggest returning for correction in the near future. This fact indicates the need to pay attention to the possible occurrence of this adverse effect when preparing a patient for surgical treatment.

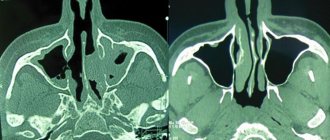

In general, issues of anthropometric changes in the anatomy of the external nose and upper lip that arise after orthognathic surgery are reflected in various research papers. According to the literature, completely different methods are used to assess changes, for example: lateral teleradiogram, clinical photography, three-dimensional laser scanning, three-dimensional reconstruction of computed tomography data or direct measurement with calipers [10, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Interestingly, there is no single opinions regarding the choice of a specific analysis technique, where each of them has its own advantages and disadvantages.

Considering the growing spread of orthognathic surgery in our country, as well as the existing interest in the problem of changing the shape of the external nose after moving the upper jaw, there is an obvious need for a more detailed study of this issue in order to improve the results of the surgical treatment we provide and, of course, improve the quality of life of our patients.

Purpose of the study.

To evaluate the possible change in the width of the terminal part of the nose after moving the upper jaw during surgical treatment of patients with anomalies of the dentofacial system.

Materials and methods of research.

The study involved 105 patients, each of whom underwent bimaxillary orthognathic surgery to correct anomalies of the dentofacial system. Patients were distributed as follows: with class III anomalies - 82 people (78%), with class II - 23 (22%), age from 17 to 36 years (average 24.3 years), women - 85 people (81%), men — 20 (19%).

Patients with trauma to the maxillofacial region and any other congenital pathology of the facial skeleton (clefts) were excluded from the study.

The treatment plan was generally accepted and consisted of orthodontic preparation, orthognathic surgery and subsequent orthodontic correction. At the same time, in 24 patients (23%), the first stage was a rapid surgical expansion of the upper jaw due to the lack of its width and, therefore, the impossibility of correct orthodontic correction of the width of the dentition.

All patients underwent movement of the upper jaw according to a standard protocol - a modified osteotomy of the upper jaw according to the Le Fort I type. After movement and subsequent rigid fixation of the upper jaw, in all cases the nasal septum was fixed along the central line by suturing it to the nasal spine, as well as suturing the base wings of the nose in order to narrow the width of the base of the tip of the nose.

To analyze changes in the width of the base of the nose, we used data from photographic registration of patients obtained at the stages before the start of treatment and 6 months after surgery. Photographs were taken with the same camera with a lens for portrait photography from a distance of 50-60 cm from the patient’s face in conditions of full room illumination on a white background.

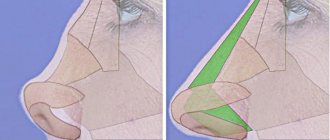

To analyze the width of the tip of the nose, we introduced two indices: the width of the wings of the nose - AWI (Alar Width Index) and the width of the base of the nose - BWI (Base Width Index). The distance between the pupils (Interpupillary distance, IPD) is taken as a constant (Fig. 1). The alar width index (AWI) reflects the percentage of the distance between the most distant points of the nasal alar (aa) in relation to the distance between the pupils. The nasal base width index (BWI) reflects the percentage of alar insertion distance (bb) relative to the interpupillary distance (IPD). Indices are presented as percentages (%). Thus, AWI index % = (aa) x (100%) / IPD and BWI index % = (bb) x (100%) / IPD. Next, the difference between the data obtained before and after surgical treatment was calculated (AWI before and AWI after; BWI before and BWI after), which corresponded to the magnitude of the change in nasal width.

Rice. 1. The distance between the pupils (Interpupillary distance, IPD) is shown in yellow, the main studied quantities are shown in green: the width of the wings of the nose - distance a-a (Alar Width Index, AWI) and the width of the base of the nose - distance bb (Base Width Index, BWI )

Statistical analysis. To carry out statistical analysis, IBM software was used - SPSS Statistics 2 and specialized methods (nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test and nonparametric Spearman correlation).

To assess the possible change in the width of the terminal part of the nose, we formulated 3 hypotheses: • Hypothesis 1. Analysis of the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in all patients (comparing “AWI before” with “AWI after” and “BWI before” with “BWI after” and assessment association between changes in AWI and BWI in all patients). • Hypothesis 2. Analysis of the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in patients with class II anomalies (comparison of “AWI before” with “AWI after” and “BWI before” with “BWI after” and assessment of the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in patients with class II anomalies ). • Hypothesis 3. Analysis of the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in patients with class III anomalies (comparison of “AWI before” with “AWI after” and “BWI before” with “BWI after” and assessment of the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in patients with class III anomalies ).

Research results.

To analyze the width of the tip of the nose, we introduced the alar width index (AWI, Alar Width Index) and the base width index (BWI, Base Width Index) and formulated three hypotheses.

Descriptive analysis of changes in the nasal alar width index - AWI (Alar Width Index) for all patients. Absolute change: average - 4.36%, median - 3.7%. Relative change - 9.42%, median - 7.44. Descriptive analysis of changes in AWI for patients with class II anomalies. Absolute change: average - 4.03%, median - 3.1%. Relative change - 8.72%, median - 7.35. Descriptive analysis of changes in AWI for patients with class III anomalies. Absolute change: average - 4.45%, median - 3.8%. Relative change - 9.62%, median - 7.49.

Descriptive analysis of changes in the Base Width Index (BWI) for all patients. Absolute change: mean - 4.67%, median - 4.2%. Relative change - 19.83%, median - 16.71. Descriptive analysis of changes in AWI for patients with class II anomalies. Absolute change: average - 3.47%, median - 2.9%. Relative change - 13.65%, median - 9.74. Descriptive analysis of changes in AWI for patients with class III anomalies. Absolute change: average - 5.01%, median - 4.95%. Relative change - 21.56%, median - 19.32.

Hypothesis 1. Analysis of the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in all patients. Comparison of “AWI before” with “AWI after” and “BWI before” with “BWI after” in all patients.

The nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare “AWI before” with “AWI after” and “BWI before” with “BWI after.” Conclusion: according to the Wilcoxon test, significance does not exceed the level of 0.001, which means that for both indicators (AWI and BWI) the “before-after” effect is statistically significant (at a significance level of 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig 2. Graphic illustration of the detected differences in AWI (A) and BWI (B) in all patients. The graph shows an increase in the AWI and BWI parameters after compared to before

Assessing the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in all patients.

Nonparametric Spearman correlation was used for analysis. Conclusion: the significance of the Spearman correlation does not exceed the level of 0.05, i.e. the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI is statistically significant (at a significance level of 0.05). The relationship between changes in AWI and BWI for all patients is direct and weak (Fig. 3).

It was also concluded that the significance of the independent variable (change in AWI) does not exceed the 0.01 level, which means that a significant influence of the change in AWI on the change in BWI was found (at a significance level of 0.01). Thus, (for all patients) with a 1 percentage point increase in the change in AWI, the increase in the change in BWI will average 0.256 percentage points, in 95% of cases this change will be from 0.077 to 0.435 percentage points. In other words, with a 10 percentage point increase in the change in AWI, the increase in the change in BWI would average 2.56 percentage points, 95% of the time the change would be between 0.77 and 4.35 percentage points.

Figure 3. Scatterplot illustrating the weak direct linear relationship between AWI and BWI change scores for all patients.

Hypothesis 2. Analysis of the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in patients with class II anomalies. Comparison of “AWI before” with “AWI after” and “BWI before” with “BWI after” in patients with class II anomalies.

To compare “before-after” indicators, the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. Conclusion: according to the Wilcoxon test, significance does not exceed the 0.001 level, which means for both indicators (AWI and BWI) the “before-after” effect is statistically significant (at a significance level of 0.001) (Figure 4).

Fig 4. Graphic illustration of the detected differences in AWI (A) and BWI (B) in patients with class II anomalies

Assessing the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in patients with class II anomalies.

Nonparametric Spearman correlation was used for analysis. Conclusion: the significance of the Spearman correlation does not exceed the level of 0.10, i.e. the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI is statistically significant (at a significance level of 0.10). The relationship between changes in AWI and BWI for patients with class II anomalies is direct and weak (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Scatterplot illustrating the weak direct linear relationship between AWI and BWI change scores for patients with class II abnormalities.

It was also concluded that the significance of the independent variable (change in AWI) does not exceed the 0.01 level, which means that a significant influence of the change in AWI on the change in BWI was found (at a significance level of 0.01). Thus, (for patients with class II anomalies) with an increase in the change in AWI by 1 percentage point, the increase in the change in BWI will average 0.459 percentage points, in 95% of cases this change will be from 0.128 to 0.790 percentage points. In other words, with a 10 percentage point increase in the change in AWI, the increase in the change in BWI would average 4.59 percentage points, 95% of the time the change would be between 1.28 and 7.90 percentage points.

Hypothesis 3. Analysis of the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in patients with class III anomalies. Comparison of “AWI before” with “AWI after” and “BWI before” with “BWI after” in patients with class III anomalies

To compare “before-after” indicators, the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. Conclusion: according to the Wilcoxon test, significance does not exceed the level of 0.001, which means that for both indicators (AWI and BWI) the “before-after” effect is statistically significant (at a significance level of 0.001) (Fig. 6).

Fig 6. Graphic illustration of the detected differences in AWI (A) and BWI (B) in patients with class III anomalies

Assessment of the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in patients with class III anomalies

Nonparametric Spearman correlation was used for analysis. Conclusion: the significance of the Spearman correlation exceeds the level of 0.10, i.e. the relationship between changes in AWI and BWI is not statistically significant (at a significance level of 0.10). There is no significant relationship between changes in AWI and BWI in patients with class III anomalies (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Scatterplot illustrating the very weak direct linear relationship between AWI and BWI change scores for patients with class III abnormalities.

Clinical examples.

All patients listed in the clinical examples underwent double-jaw surgery (orthognathic surgery) according to a standard protocol, namely: a modified LeFort I Osteotomy (LFO) and a bilateral sagittal splitting osteotomy of the lower jaw (Bilateral Sagittal Splitting Osteotomy, BSSO). Also, after fixing the upper jaw, in all cases the nasal septum was fixed along the central line by suturing it to the nasal spine and suturing the base of the nasal wings (Alar Cinch Technique) in order to narrow the width of the base of the terminal section of the nose.

In all clinical case drawings (Fig. 8, 9, 19, 11 and 12), the initial width of the nasal wings (distance a-a) is shown by green long lines, the initial width of the base of the nose (distance bb) is shown by green short lines. The postoperative width of the nasal alae (distance a-a) is shown by the red long lines and the postoperative width of the base of the nose (distance bb) is shown by the red short lines, respectively.

Rice. 8. A patient with class II development of anomalies of the dentoalveolar system, distal occlusion. The increase in the width of the wings of the nose was 13.6%, the width of the base of the nose - 8.2%

Rice. 9. Patient with class III development of anomalies of the dentoalveolar system, mesial occlusion. The increase in the width of the wings of the nose was 7.2%, the width of the base of the nose - 10.3%

Rice. 10. A patient with class II development of anomalies of the dentoalveolar system, distal occlusion. The increase in the width of the wings of the nose was 10.5%, the width of the base of the nose - 3.1%

Rice. 11. A patient with class II development of anomalies of the dentoalveolar system, distal occlusion. The increase in the width of the wings of the nose was 10.1%, the width of the base of the nose - 7.4%

Rice. 12. A patient with class III development of anomalies of the dentoalveolar system, mesial occlusion. The increase in the width of the wings of the nose was 10.9%, the width of the base of the nose - 3.9%

Discussion of the results obtained.

Movement of the upper jaw inevitably affects changes in the anatomy of the external nose. Considering the fact that the nose is one of the main components of the aesthetic perception of the face, issues related to changes in its anatomy are quite relevant and require more in-depth study. Also, the importance of this problem is sometimes pointed out to us by patients themselves, who contact us some time after a successful orthognathic operation to discuss possible rhinoplasty, which is associated with postoperative changes in its morphology.

Thus, the data we obtained on changes in the width of the base of the nose and the width of the wings of the nose in 105 patients indicate a statistically significant increase in these values after surgery in comparison with the values before surgery. Thus, the absolute value of the change in the width of the wings of the nose averaged 4.36%, the relative value - 9.42%, and the absolute value of the change in the width of the base of the nose averaged 4.67%, the relative value - 19.83%. In all patients, the technique of suturing the base of the nasal wings was used, and not a single patient had any additional interventions on the structures of the external nose. Thus, our results are comparable with the literature.

For example, according to a number of authors [2, 3, 6, 7, 18, 19], when moving the upper jaw, there is always a change in the morphology of the entire external nose and, in particular, its terminal section, and an increase in the width of the base of the nose is always observed when moving the upper jaws, especially in patients with class III anomalies of the dental system. Also an important factor is the features of the surgical protocol. For example, when creating access and for subsequent fixation of the displaced jaw, a wide detachment of the soft tissues of the middle zone of the face is carried out, including around the pyriform opening. These manipulations deprive soft tissues of support, which leads to the possibility of their movement and, as a result, changes in the anatomy of this area. As a result, there is a change in the morphology of the terminal part of the nose, always in the direction of its expansion to one degree or another [6, 7, 19]. In addition to the above factors, the severity of changes in the terminal part of the nose after moving the upper jaw is also influenced by others, namely: the amount of jaw movement, the tone of the facial muscles and the thickness of the skin [2, 6, 10, 13].

However, there are a number of surgical techniques that are aimed at correcting this unfavorable effect. The most common and also used by us is the technique of stitching the base of the wings of the nose (Alar Cinch Technique). Of course, it makes it possible to narrow the width of the tip of the nose, but nevertheless it is often insufficient. Moreover, excessive contraction of the base of the nasal alae can lead to a significant narrowing of the tip of the nose, impaired nasal breathing function and an aesthetically unfavorable change in the anatomy of the upper lip [7, 9]. However, according to a number of authors, the use of various surgical techniques cannot guarantee the final result, which always remains unpredictable [18]. Moreover, Dr. Betts NJ and colleagues in their study point to the possible asymmetry of the wings of the nose as a result of the use of the technique of suturing the base of the wings of the nose and provide data that there is practically no difference in the change in the width of the base of the nose when comparing two groups of patients: those who underwent suturing of the base was also performed for those who did not undergo it [21]. Also, a number of authors have proposed various modifications to the technique of suturing the base of the nasal wings in order to improve the postoperative result [8, 12, 14]. But it was noted that the result almost always remains not entirely predictable.

To summarize, we can say that the above facts tell us about the need to improve existing surgical techniques, as well as to develop additional techniques and protocols aimed at reducing such an unfavorable effect of orthognathic surgery as widening the base of the nose.

Conclusions.

According to our research, it was proven that during the movement of the upper jaw, there is always a change in the morphology of the end of the nose, namely its expansion. The low effectiveness of the technique of suturing the base of the wings of the nose has been proven.

Bibliography.

Bezrukov V.M. Clinic, diagnosis and treatment of congenital deformities of the facial skeleton: Dis... Dr. honey. Sci. - M., 1981, -329 p. 2. Gunko V.I. Clinic, diagnosis and treatment of patients with combined jaw deformities: Dissertation... Dr. honey. Sci. - M., 1986, -525 p. 3. Kalmykov A.V. Prevention of nasal deformities after bone reconstructive operations on the maxillary complex: Dissertation... Cand. honey. Sci. - M., 2002, -132 p. 4. Glushko A.V. Assessment of morphometric changes in the upper respiratory tract in patients during orthognathic operations: Dissertation... Cand. honey. Sci. - M., 2013, -245 p. 5. Glushko A.V., Gordina G.S., Drobyshev A.Yu., Serova N.S., Fominykh E.V. Application of MSCT data for aesthetic assessment of the shape of the nose // Russian Electronic Journal of Radiation Diagnostics. - 2014. - T. 4. - No. 2 - P. 66-74. 6. Bell WH: Le Fort I osteotomy for correction of maxillary deformities. J Oral Surg 33: 412-426, 1975 7. Altman JI, Oeltjen JC: Nasal deformities associated with orthognathic surgery: analysis, prevention, and correction. J Craniofac Surg 18: 734–739, 2007 8. Mommaerts MY, Abeloos JVS, De Clercq CAS, Neyt LF: The effect of the subspinal Le Fort I-type osteotomy on interalar rim width. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg 12: 95-100, 1997 9. Rosen HM: Lip-nasal aesthetics following Le Fort I osteotomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 81: 171-182, 1988 10. Chung C, Lee Y, Park KH, et al: Nasal changes after surgical correction of skeletal class III malocclusion in Koreans. Angle Orthod 78: 427–432, 2008 11. Collins CC, Epker BN: The alar cinch: a technique for prevention of alar base flaring secondary to maxillary surgery. Oral Surg 53: 549-553, 1982 12. Schendel SA, Williamson LW: Muscle reorientation following superior repositioning of the maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 41: 235–240, 1983 13. Westermark AH, Bystedt H, Von Konow L, et al: Nasolabial morphology after Le Fort I osteotomies. Effect of alar base suture. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 20: 25-30, 1991 14. Shams MG, Motamedi MHK: A more effective alar cinch technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 60: 712-715, 2002 15. Waite PD, Matukas VJ: Indications for simultaneous orthognathic and septorhinoplastic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 49: 133-140, 1991 16. Ghali GE, Sinn DP: Nasal surgery an adjunct to orthognathic surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 8: 33-43, 1996 17. Donatsky 0, Bj0rn-j0rgensen J, Hermund NU, et al: Accuracy of combined maxillary and mandibular repositioning and of soft tissue prediction in relation to maxillary antero-superior repositioning combined with mandibular set back. A computerized cephalometric evaluation of the immediate postsurgical outcome using the HOPS planning system. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 37: 279–284, 2009 18. Park SB, Yoon JK, Kim YI, et al: The evaluation of the nasal morphologic changes after bimaxillary surgery in skeletal class III malocclusion by using the superimposition of cone-beam computed tomography ( CBCT) volumes. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 40: 87–92, 2012 19. Park SB, Kim YI, Hwang DS, Lee JY: Midfacial soft-tissue changes after mandibular setback surgery with or without paranasal augmentation: cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) volume superimposition. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 41: 119–123, 2013 20. Farkas LG: Anthropometry of the head and neck. New York, NY: Raven Press, 1994 21. Betts NJ, Vig KWL, Vig P, et al: Changes in the nasal and labial soft tissues after surgical repositioning of the maxilla. Int. J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg 8:7-23, 1993

Rehabilitation after surgery

During the first few days you will have to wear a splint bandage and endure tampons in your nose. You can leave the clinic a few hours after the end of the operation. The swelling goes away quite quickly, and nasal breathing is restored in about a week.

In most cases, rehabilitation lasts no more than 10 days. As a rule, after correcting the shape or size of the wings, the patient can safely appear in public after 4-5 days; after autocartilage transplantation, after 7-10 days.

The seams will remain visible for some time. There is no need to worry: in just a month they will be easily disguised with cosmetics, and in a few more months they will turn into invisible threads (provided the surgeon is well trained).

Rehabilitation

After the operation, the patient requires comprehensive rehabilitation. It largely depends on the volume of intervention and the type of operation. On average, it will be possible to evaluate the first results no earlier than 2-4 weeks after the operation, when the swelling gradually begins to subside. Free nasal breathing will be restored within a period of up to 2-3 months, as the structure of the mucous and submucosal layer is restored and swelling of the cartilage is eliminated. With revision rhinoplasty, the recovery process will be two to three times slower.

During the rehabilitation period, thermal procedures, solariums, tanning on the beach, baths, and saunas are prohibited. It is worth refraining from smoking and alcohol. It is important to strictly follow all doctor's recommendations regarding nutrition, temperature and type of food.

In the first weeks, you need to avoid blowing your nose, physical exertion and injuries to the nasal area, and adjust the intake of any medications, discussing them with the operating doctor.

Non-surgical modification of the wings of the nose

Many people understand that we are talking about contour plastic surgery, that is, changing the shape or size of the wings by adding volume with fillers. The method gives a temporary effect, the duration of which is from six months to one and a half years (depending on what kind of fillers are injected and how quickly they leave the body). This option may become relevant in cases where it is necessary to correct recession or insufficient thickness/width of the nostrils.

For some of our patients, filler injections become a kind of “rehearsal” before surgery: they can live with the new nose, evaluate the appearance and make a final decision about the need for a full-fledged operation.

What types of nose shapes are there?

The nose consists of bones, cartilage and epithelium. These elements form the nasal cavities and the upper part - what we see when examining a person. All babies are born with small noses, but as they grow, their noses acquire such hereditary characteristics as: shape, width, length, hump. Looking at the nose in more detail, it can be noted that noses differ in shape, length, width, shape of the tip, “wings” of the nose, base and back. The profiles of the human face can be different due to different nose shapes:

- humpback (slightly “broken” profile),

- hook-shaped (the tip of the nose “looks” down),

- aquiline (such a nose has a slight curvature),

- Roman (hump present),

- Greek (the nose starts from the forehead, there are practically no depressions),

- button (small and round nose, the tip of the nose “looks” upward, but the nostrils are still not visible),

- nose turned up (the bridge of the nose is concave inward),

- upturned (the tip of the nose “looks” upward),

- funnel (this type of nose is most often found among representatives of the Negroid race).

The bridge of the nose can be straight, concave, wavy, convex. The dorsum comes from the base of the nose, that is, from the deepest part of the bridge of the nose. And the width of the back of the nose in the upper part of the nose is equal to the width of the seams of the nasal bones, and in the middle part the width of the back of the nose is similar to the size of the pyriform opening. The wings of the nose, more precisely, their most protruding part, conditionally touches the plane in which the fangs of the upper jaw are located.

The base of the nose can be rounded, blunt, sharp and round. Experts also distinguish the following options: horizontal, raised and lowered bases. In forensic science, there are several shapes of the tip of the human nose: wide, thin, medium. It should be noted that those with a nose that has a short subnasal suture and a wide pear-shaped opening, as a rule, have a wide tip of the nose, while those with an elongated and narrow subnasal spine have a pointed tip of the nose. Based on the angles of inclination, noses are distinguished between horizontal, raised and lowered. The angle formed between the upper lip and the lower part of the nose indicates the level of intelligence of a person. Thus, a right angle indicates a high level of human intelligence, and if this angle is obtuse, this means that the owner of such a nose is distinguished by a non-trivial mind.

How much does it cost to surgically change the wings of the nose?

For correction of the wings of the nose, the price depends on the complexity of the work, which is assessed by the surgeon during a personal examination. In any case, such a laser operation will cost an order of magnitude cheaper than a full-fledged nose job involving bone structures. When combining rhinoplasty of the wings of the nose with correction of the nasal septum, the amount is calculated on an individual basis.

The feasibility of correcting only the wings of the nose is considered based on a combination of several factors: the original shape, size of the nose, the presence of defects, the wishes of the patient (patient), the result that intervention on the wings of the nose will give. Sometimes the surgeon stops at this option for nose correction, in other cases he suggests supplementing it with plastic surgery of the tip or back, or immediately speaks of the need for a full-fledged rhinoplasty.

Have questions? Call and come!

Causes of large nostrils

Sometimes the appearance of the nose differs significantly from ideal proportions. Changes in the back, tip, size and shape of the nostrils, the length of the nose and its proportions in relation to the face are possible due to two groups of reasons:

- Congenital anomalies and structural features. They arise in utero when the facial skeleton and nasal cartilage are formed. If the process is disrupted at one stage, a crooked nose, widening of the nostrils, excess growth of cartilage and a hump may occur.

- Acquired anomalies. They arise already in life, from early childhood to old age. These could be unsuccessful surgical operations on the face or in the nasal area, serious injuries, curvature of the nasal septum, defects in the development of the facial skull due to adenoids, constant swelling and hypertrophy of the mucous membrane, polyps, etc.

Defects can affect the bone, cartilaginous part of the nose, and soft tissues. Separately, it is worth noting the defect when one nostril is larger than the other. It can also be corrected during rhinoplasty.